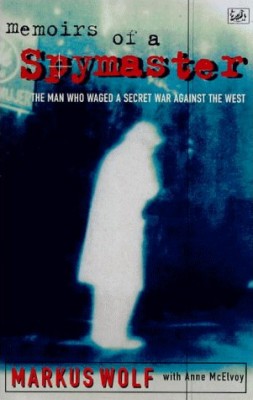

This is a review for the 1997 autobiography of Markus Wolf, the former head of East Germany’s foreign intelligence department.

Wolf’s story begins with a fascinating personal history, particularly, regarding his father who was a communist and their exile from Nazi Germany in Moscow. After the end of WWII and the downfall of the Third Reich Wolf returns to Germany, to Berlin, taking a position first as a journalist in the Soviet Zone and later taking a position and rising through the ranks of the party. He eventually becomes and serves for 30 years as head of the foreign intelligence division, the Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung (HVA) (en. Main Reconnaissance Administration), within the Ministry for State Security.

I found the writing articulate, though it often provides too much detail. It is especially riddled with justifications for controversial actions on the part of himself or the DDR. For example, there is a whole chapter devoted to Willy Brandt, the Chancellor of West Germany who resigned when one of his aides was exposed as an East German spy.

For all the dull details of his bureaucratic life …

“Vast stretches of this work were very boring. Intelligence is essentially a banal trade of sifting through huge amounts of random information in a search for a single enlightening gem or illuminating link.” (101)

… the book also contains a unique historical perspective of WWII and the two German states during the Cold War. It also has many other interesting facts about pre-digital-computer surveillance including methods for protecting identities of spies and ways to physically transfer secret messages. One example, which would be easy with a computer’s ability to generate pseudo-random numbers, was the use of bank note serial numbers for random numbers in cryptographic messaging. He mentions often that he was not a fan of the use of the computer to automate details of record-keeping or gathering because he felt computer records could to easily be stolen and put into the wrong hands.

“The problem with technical intelligence is that its essentially information without evaluation.” (284)

In closing, I recommend this book to anyone interested in the historic details of East Germany’s Ministry for State Security. I’ll end with a few choice quotes which point to the author’s wisdom and ability for critical self-reflection.

“The dividing line between freedom fighters and terrorists is usually determined by which side you are on.” (279)

“No secret service can ever be democratic nor, … open to constant scrutiny.” (282)