Credit: Museum in der Runde Ecke

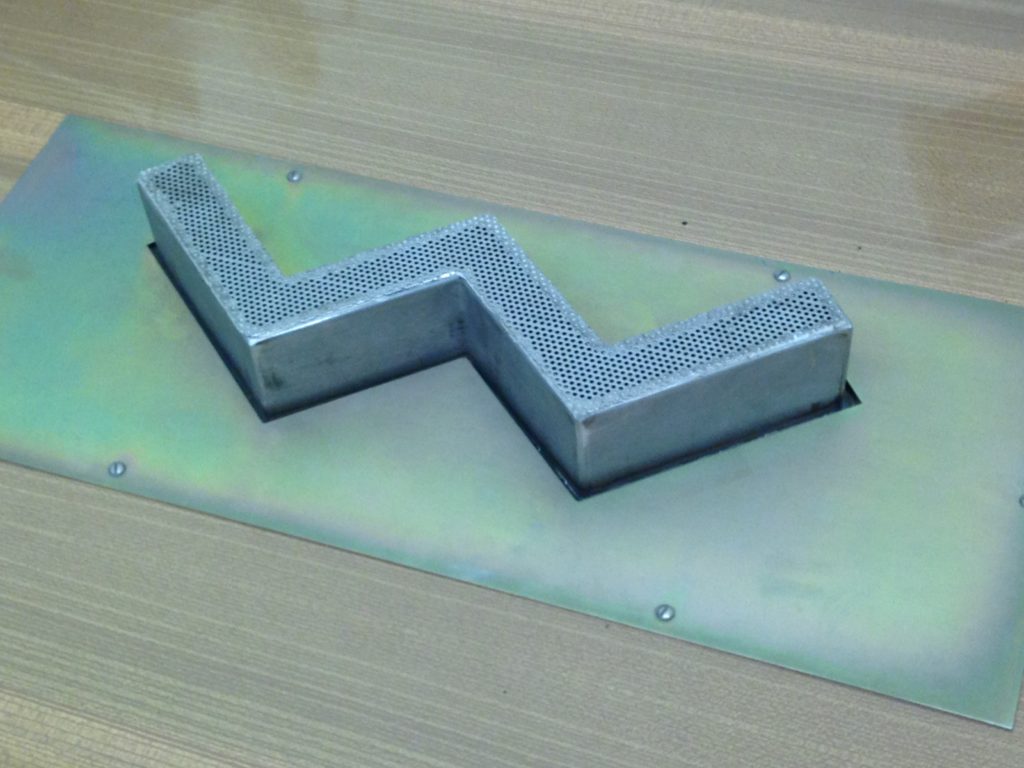

If the “W”-shaped, two-letter steam distribution grid was an “upgrade,” then the ultimate “deluxe” Stasi steam device for manually opening letters with hot water vapor is the “Arbeitstisch der Heißdampf-Öffnungsanlage 532” (English: Work Table for Hot Steam Opening System 532). This modular table was constructed for Department M by the Operational-Technical Sector (OTS) of the MfS in the late 1970’s for manually steaming open envelopes with water-soluble adhesives. The Museum in der Runde Ecke has two of these modified working tables. There is no information on whether “532” is the model number or series number (which would imply there were 531 other models!), and unfortunately I did not record the plate on the front last time in Leipzig, so I cannot confirm its contents until I return.

Credit: Museum in der Runde Ecke

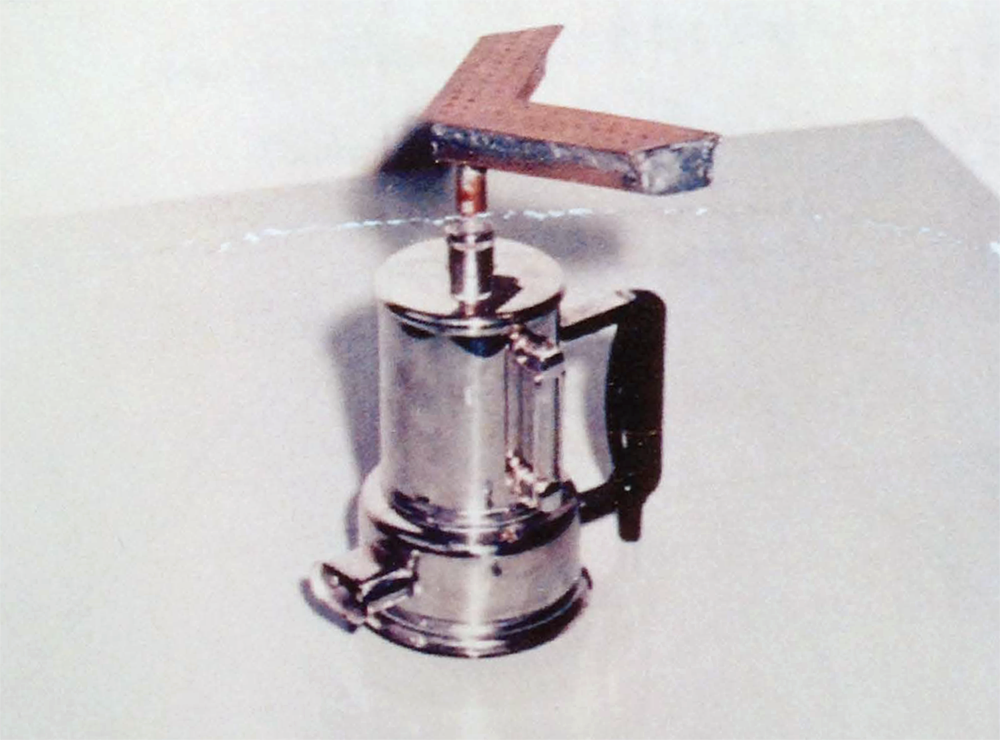

One of the Runde Ecke tables has its own power supply which could be connected to up to three other units to supply power in series (a.k.a. “daisy chaining”). In the center of each table is a “W”-shaped vapor dispersion grid on which two envelopes could be placed. Under the plate is the steam generator, which contained a heater, water storage, and float. While in operation a storage vessel for distilled water was placed underneath. The unit was operated by turning the rotary switch (positions: 0 = “off”, 1 = “pause”, and 2 = “full”) on the attached control panel. Two control lights indicated the operating state of the table, a yellow light which lit when the table was on, and a red light which illuminated when the float inside the steam generator detected that the water was low.

Credit: Museum in der Runde Ecke

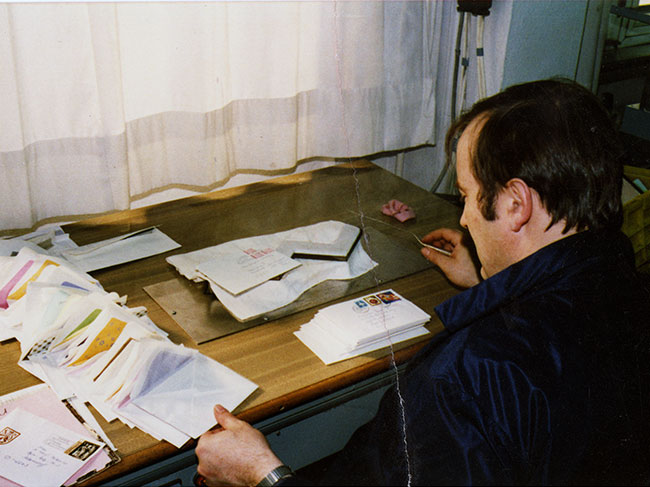

To use the table MfS staff turned the steam generator dial to the “full” position. This activated the heater inside the water receptacle. Once the water reached the correct temperature and began to evaporate the staff placed the flap of the letters on the angles of the W-shaped mesh grids. The vapor, which could reach temperatures of to 100ºC, emerged from the W and dissolved the adhesive. A towel was stretched over the opening to prevent water buildup. Up to 100 letters (between private citizens of the GDR) per hour could be opened on this device.

Stasi staff using the “Work Table for Hot Steam Opening System 532.” Credit: BStU, MfS, Dept. M, Fo 0031, figure 0003

Of the devices I’ve examined so far, this table has little outright evidence that it contains modified parts. Unlike the “hacker aesthetic” of other devices, attention has been given to the various additions to the table to match them to the original. The control panels use commercially-available switches and indicators and are constructed with sheet steel and painted to match the bluish grey steel of the tables. The “W” mesh steam dispersion grid appears to be constructed of aluminum or another treated metal that would not oxidize, and is attached to the table using a plate with measured and symmetrical fasteners. Like the Stasi organization itself, which over time refined their methods according their ideology and what was available, the sharp edges and reused parts on this transformed table are concealed to match the professionalism, efficiency, and attention to detail with which the workers were expected to perform their tasks.

- Work Table for Hot Steam Opening System 532 (Inventory no. 00007). Objekt- und Fotodatenbank Online im Museum in der Runden Ecke. Accessed June 10, 2017.

- Work Table for Hot Steam Opening System 532 (Inventory no. 00354). Objekt- und Fotodatenbank Online im Museum in der Runden Ecke. Accessed June 10, 2017.

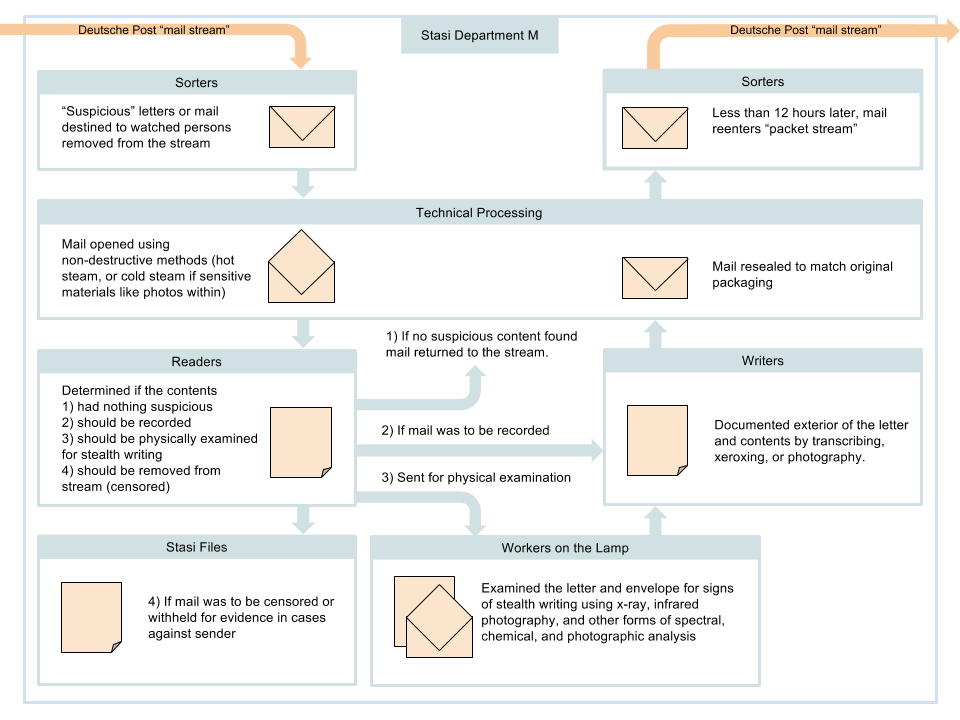

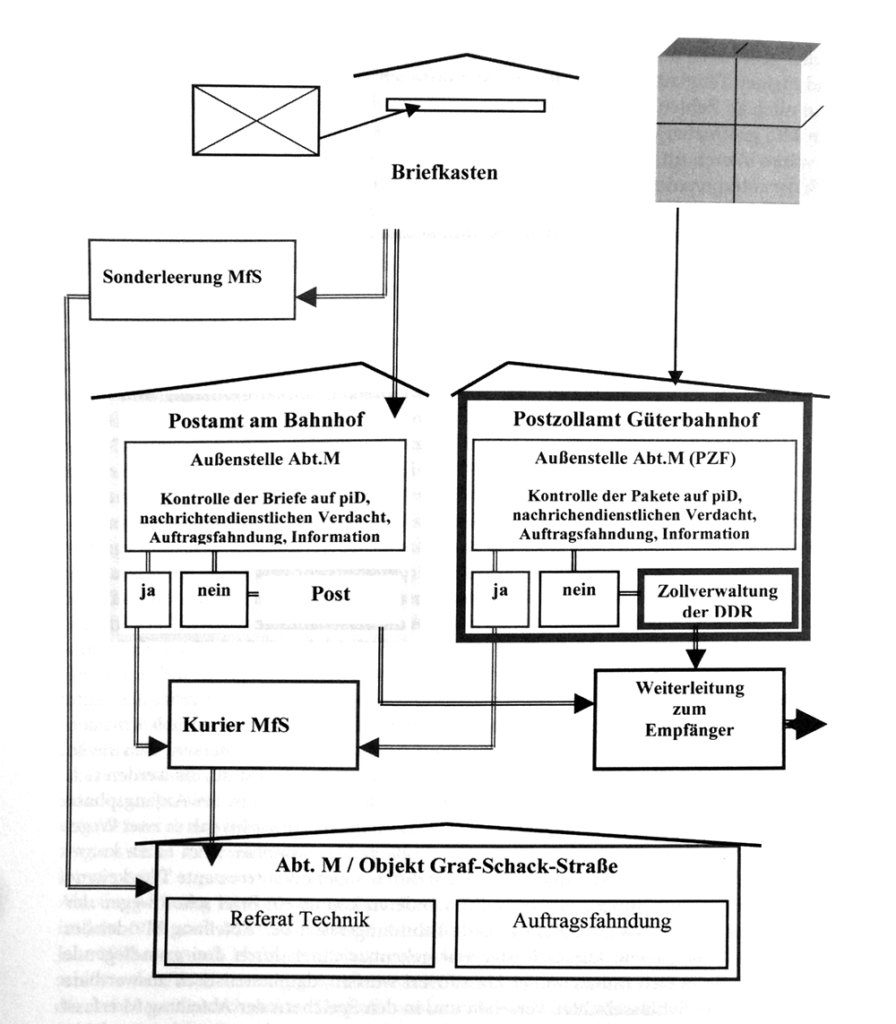

- BStU. Die Stasi und das Postgeheimnis. Accessed June 10, 2017.