One of the first items on my sabbatical to do list last year was to convert the Camp La Jolla Military Park website to a static Jamstack site hosted at Github Pages. This post documents that process.

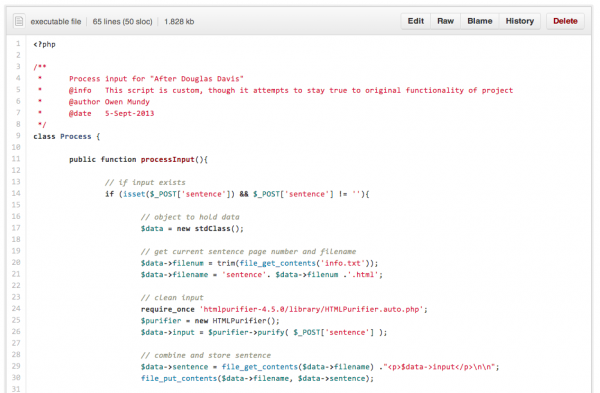

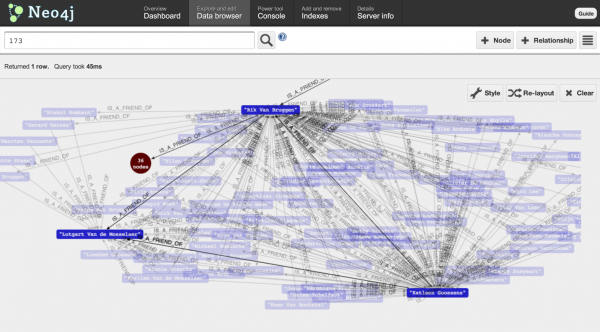

I originally created the site as a research tool using PHP and a MySQL database for data entry, to record, organize, and ultimately publish research about the military history of UCSD. Moving the project to Github Pages would simplify maintenance and hosting costs, but was no small task. Technically it didn’t cost me extra to host, but the domain was $20/year, which adds up. Further, maintaining a PHP/MySQL website with a custom admin tool requires a bit of overhead for security and updates. Additionally, I wanted to continue having the benefit of using template engines or some way to include files (like PHP’s require()) to save time coding the site.

There are a plethora of tools available to publish a database-driven site on a static host. They mostly can be categorized as follows (ordered by most to least dynamic data sources):

- Move the database to a remote service like Firebase, Atlas, et al. — ⚠️ Ultimately creates vendor lock-in, potential hidden costs, and probably more maintenance issues in the future.

- Create a static version of the database by converting MySQL to flat files (JSON, CSV, etc.), which still allows for querying using one of various tools — 🤔 This method is interesting, because it still decouples the data from the presentation and allows for potentially more options later, including a remote database. I am already using this in various forms but worry again about maintenance, or issues with the client’s ability to manipulate the data as needed.

- Generate a static version of the site, including all its pages which contain the data formerly dynamically inserted from MySQL. — 🤔 I like this concept, and have been using it to auto-publish my class lectures and tutorials using Markdown and Grunt with Marp. Plus, there are many site generators to choose from, which I explore below.

- Scrape the site and save pages as static files. After all, everything is static once the HTML is rendered on the frontend. — ⚠️ While fast, this requires the site be built first and would make updates difficult.

Essential Concepts

Here I outline some concepts on rendering. See SSR vs CSR vs ISR vs SSG for a more in-depth look:

- Client-Side Rendering (CSR) (e.g. Single-Page Application (SPA)) – JS renders pages in client’s browser with empty HTML files + raw data from the server. (e.g. React, Vue, Angular)

- Server-Side Rendering (SSR) (e.g. Fullstack) – Generates pages on server with dynamic data before delivering to client. Improves SEO and loading, decreases server performance. (e.g. EJS, PHP, or Next.js)

- Static Site Generation (SSG) (e.g. JAMStack) – Pre-renders all pages as static HTML during build process. Fast loading times, enhanced security, and dynamic content can still be achieved via “islands”.

- Incremental Static Regeneration (ISR) – Combines SSR and SSG to pre-render static pages during build time while periodically regenerating specific pages with updated data.

- Edge-Side Rendering (ESR) – Rendering process is pushed to the CDN’s edge servers which handles requests and generates HTML. Requires Nitro engine.

Requirements

Requirements for most of the projects I mention above.

- Javascript-based

- The data will be static, but editable using Git

- The data should be searchable using a tool like chosen

- The site design will be simple, but I should have creative control

- The site will be public, and be presented mostly using the same design as the original site

- HTML/CSS validation + Accessibility checks

- Convert from Google Maps to Leaflet

- Host the site on Github Pages

While planning the project I also wanted to select a method I could use for other potential static (or nearly static) sites like:

- A new site documenting the hundreds of examples and overlapping categories of Critical Web Design and internet art I’ve been collecting for an upcoming book. Update: I built it with SvelteKit

- Converting tallysavestheinternet.com to a static site (currently SSR) and unlinking the extension from the server to use local data only

- Moving away from WordPress more generally (and its security problems) and blogging with Markdown instead, starting with this blog (NO MORE TYPING IN A WEB FORM!!)

It’s nice to learn new tools. I already have some experiences with React, Next.js, and Vue.js, but wouldn’t say I’m confident in any. I found that publishing apps using React Native is very frustrating and unreliable, and my general distrust of Facebook makes me lean towards Vue. Still, I went in with with an open attitude.

Tool Comparison

A breakdown of some tools I considered. Some of the icons are clickable…

| Framework | SPA | SSR | SSG | MD | Themes | Search | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jekyll | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ? | ❌ Ruby |

| Hugo | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ? | ❌ Go |

| Astro | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | React, Vue, Svelte in dynamic islands, simple routing |

| Vue.js | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ? | ✅ vuepress |

| Nuxt.js | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ? | Built on Vue |

| SvelteKit | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | MD rendering not native but supported via MDX |

| Next.js | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | MD rendering not native but supported via MDX |

Next

My experience with Next.js SSG was painful.

- Constantly running into subtle changes in syntax across versions

- Adding an image is ridiculously difficult.

- Exporting the SSG ultimately created dead links, packaged up in Next code that was hard to understand.

- So much automation to make a static site in the end you can’t do anything unless you have the exact right code, in the right version, in the right paths.

- Error messages are rarely helpful or pinpoint the line number causing the issue in the stack.

- I followed so many tutorials that ultimately ended in dead-ends, incorrect versions, or that completely didn’t work.

Astro

I ended up choosing Astro for the final project, which can be seen here https://omundy.github.io/camplajolla/. While they appear to have many similarities, I found Astro soooooo much easier than Next.js. It’s fairly simple to install, even using a starter theme, and it didn’t take long torip out tailwind to add bootstrap.